|

In the period between 1998 - 2002, when an international market raised a strong interest in Moroccan Henna textiles, the veils of the Ahel Telt were among the most demanded types. The Ahel Telt live in the most northern part of the Middle Atlas as a part of the Beni Ouarain confederation. Their territory is situated east + southeast of the Jebel Tazzeka + south of the Oued Msoun valley. Similar to the surrounding neighbours of the Beni Ouarain confederation the Ahel Telt used to live mainly from semi-nomadic cattle breeding in the past. The information given in this text on the Ahel Telt women's veils is based on the results of field documentation trips to the region that I did with my long time partner Mustapha Hansali in the years between 1994 - 2001. As an educated linguist, Mustapha Hansali is also a native tamazight speaker who lives + works in Morocco. The regional terminology used in the text on the Ahel Telt textiles is in tamazight (the regional Berber language), unless otherwise noted. The contribution on the veils of the Ait Haddidou is provided by Henri Crouzet, Paris.

The Quest for Clarity © Gebhart Blazek + Henri Crouzet Following the ‘hype’ around Moroccan Berber textiles in the late 1990s and the first years of the following decade, the publication of 'Costumes Berbères du Maroc' by Marie Rose Rabaté and Frieda Sorber in late 2007, gave us hope that this book would bring much needed clarity and structure to the matter. Such clarity and structure was the stated goal of this opus, at least according to Marie Rose Rabaté, who does not tire of asserting her claim to them in her chapters. Unfortunately her claim is met in very few areas, and chapters that from their titles promise much, offer mainly speculative assumptions and even misinformation. In ‘Berber Style’, for instance, Rabaté boils the entire iconography of Berber textiles down to a few basic motifs, especially anthropomorphic figures. But this interesting idea remains nothing but an assertion, and it is unsupported by any in-depth argument.

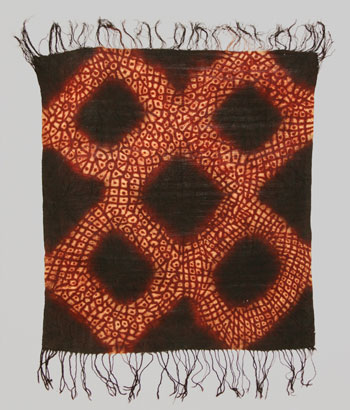

Even more problematic is her attempt in ‘Seduction and Pitfalls of Authenticity’ to clarify the differences between ‘authentic’ Berber textiles and those which have in the broadest sense been made for the market. This is an honourable effort, but there are good reasons why no one has ever succeeded in dealing with this subject in the requisite depth and breadth, which would involve accurate observation of a multitude of cultural traditions, stylistic characteristics, technical processes and other factors. In contrast to Rabaté’s reductionist analysis, one would need to produce comprehensive documentation and analysis of at least thirty securely known types of genuine traditional textiles, as well as many others that have emerged on the market in recent times for which a traditional source and usage are not traceable. Let us take a closer look at two of the many types of Berber tribal textiles addressed by Rabaté: the 'tarredat' or 'taritat' veil of the Ahel Telt from the Beni Ouarain Confederation in the northeastern Middle Atlas and the tie-dyed 'agounoun' shoulder scarf of the Aït Yazza, an Aït Hadiddou sub-tribe living in the central High Atlas around Imilchil (1). |

|

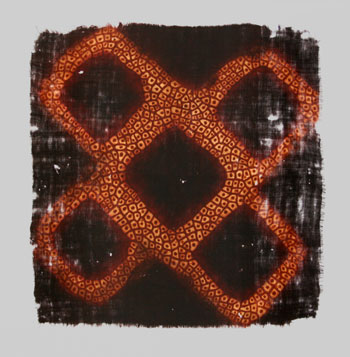

(1) shoulder scarf 'agounoun', Aït Haddidou, central High Atlas, Morocco, mid 20th c., tie-dye on a wool fabric, 68 x 68 cm (27'' x27'') |

| For the 'agounoun', Rabaté asserts a conspiracy by traders who imported textiles from Libya to Morocco to sell to gullible tourists and dealers as rare and expensive items of Moroccan origin. She is clearly unaware of the research on Aït Hadiddou tribal practices undertaken between 1970 and 1990 by the Austrian ethnologists Norbert Mylius Sr. and his son Norbert Mylius Jr. who, in 1970, filmed a documentary entitled Aït Haddidou (North Africa, High Atlas) – Dyeing a Cloth with the Plangi Technique (released in 1974 by IWF Wissen und Medien, Göttingen ). This shows in detail how an Aït Hadiddou woman produced a tie-dyed 'agounoun' using a piece of fabric cut from an old weaving (2). In 1985, Mylius also filmed the last mass wedding ceremonies of the Aït Hadiddou. His film, Timghriwin: Mass Marriage of Berbers in the Atlas Mountains – Marriage Destined for Divorce, clearly shows how the 'agounoun' was worn on the bride’s shoulders, over her handira (shawl) and under her hair. No more than a brief internet search and a little time was required to find this work, which more than confirmed our own field observations in 2001. |

|

| (2) The dyeing procedure of an Aït Haddidou 'agounoun' documented 1970 by Norbert Mylius (sen. + jun.) in situ in the village Ait Ali ou Ikkou near Imilchil. (after the closing of the IWF Goettingen the film is currently not available online. Please get in contact with us if you need closer information about the Mylius films or seek to find a copy) |

| For the Beni Ouarain 'taritat' or 'tarredat' veil, documentation is more difficult and complex. Here again Rabaté assumes a dealer’s conspiracy to deceive naïve collectors. She states that counterfeit examples are easy to identify since the basic fabric is of recent origin, in good condition, with both lateral borders and fringes intact, whereas the ground fabric of authentic older pieces has been cut from a much larger wrapping cloth, and should thus show cut edges. In support of this argument she cites a 1938 article by Marcel Vicaire, the former Directeur des Arts Indigènes au Maroc, in which he describes the manufacture of these headscarves, mentioning that the ground fabric is usually cut from old wrapping cloths (“Le tissu, en mousseline de laine, armure toile, est généralement un vieux 'haïk dans lequel la femme coupe un rectangle d'environ 1 mètre sur 1 mètre 30”). Where objects are traded at high prices, when a product becomes sufficiently profitable, forgeries can appear. But it is unacceptable, and highly counterproductive, to assume overall imposture and counterfeiting, without detailed knowledge of the matter. Recent copies of these headscarves exist that attempt to imitate the technical and aesthetic qualities of the original old textiles on the market, and at least some of them were made from recently produced materials. But it’s also true that authentic textiles of this group exist. Condition alone cannot provide reliable information about the true age of the piece. It is apparent that during her ‘research’, Rabaté had access to very few pieces, all in good condition, which she found suspicious. At least a couple of dozen authentic headscarves from the Ahel Telt region from about 1900 and 1950 are known to survive, as well as a similar number of wrapping cloths (arab. 'haïk'), a larger quantity of attendant headbands, and many shoulder covers or shawls of the 'tabrdouhte' or 'tabbnoute' type, which continued to be made in the traditional manner up to the late 1970s (3) - (19). |

|

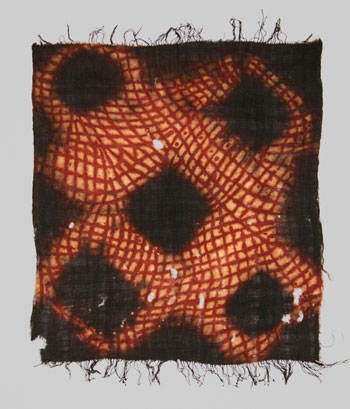

(3) women's veil 'taritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 96 x 100 cm (38'' x 39,5''). Tie-dye and henna painting on a wool fabric. C14 tested by ETH Zuerich (ref. ETH 35059) to have been woven between 1963 - 1965 (see analysis details below)

|

|

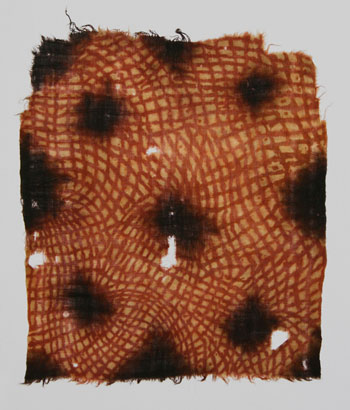

(4) women's veil 'taritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 83 x 98 cm (32,7'' x 39''). Tie-dye and henna painting on a wool fabric. First half 20th cent. |

|

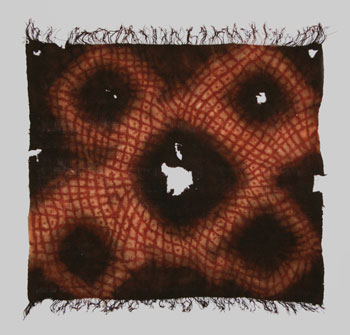

(5) women's veil 'taritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 107 x 97 cm (42'' x 39''). Tie-dye and henna painting on a wool fabric. First half 20th cent. |

|

(6) women's veil 'taritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 114 x 101 cm (44,9'' x 39,7''). Tie-dye and henna painting on a wool fabric. Early / first half 20th cent. |

|

(7) women's veil 'taritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 108 x 124 - 130 cm (42,5'' x 48,8'' - 51,2''). Tie-dye and henna painting on a wool fabric. ca. 1900 / early 20th cent. |

|

(8) women's veil 'taritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 126 x 130 cm (49'' x 51,2''). Tie-dye and henna painting on a wool fabric. 19th cent. |

|

(9) women's veil 'taritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 128 x 115 cm (50,4'' x 45,3''). Tie-dye and henna painting on a wool fabric. mid 20th cent. |

|

(10) women's veil 'taritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 102 x 99 cm (40,2'' x 39''). Tie-dye and henna painting on a wool fabric. first half 20th cent. |

|

|

(11) women's headbands 'tachedat n'tritat', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, weaving length ca. 45 - 65 cm (17,8'' x 25'') / overall length incl. fringes ca. 150 - 170 cm (ca. 60'' - 65''), early / first half 20th cent. |

|

(12) women's artificial braids made from wool, Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, overall length ca. 80 cm (ca. 32''), first half / mid 20th cent. |

|

|

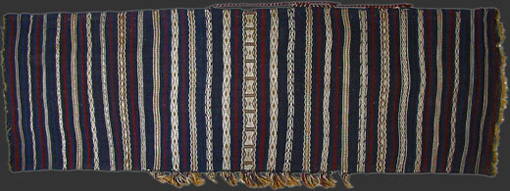

(13) women's shawl 'tabrdouhte' (arab. handira), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 248 x 84 cm (97,6'' x 33''), late 19th / early 20th cent. This example contains a considerable amount of linen yarn (2 ply hand spun) in the white design parts, a material that has been quickly substituted in the Ahel Telt region by fine industrial cotton yarns (3 ply machine spun) around the end of the 19th century. Colors seem to be all natural. Therefor one may conclude that the piece is from a period around 1900 or slightly earlier although in almost perfect condition. for detail see >> (32) |

|

|

(14) women's shawl 'tabrdouhte' (arab. handira), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 235 x 85 cm (92,5'' x 33,5''), around 1900. This example contains only fine industrial cotton yarns (3 ply machine spun) in the design parts. The colours are predominantly natural but one can also find small amounts of early synthetic dyes, namely a Fuchsin violet (a colour that had been invented in 1858 and that has been available in the remote areas of the Middle Atlas from the end of the 19th century on). Although this piece looks much more worn than the previous one, one can only conclude that the period of production is most likely not before ca. 1900. for detail see >> (33) |

|

|

(15) women's wrapping textile 'tahraoukht' (arab. 'haïk'), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 420 x 130 cm (165,4'' x 51,2''), early 20th cent. This example contains only fine industrial cotton yarns (3 ply machine spun) in the design parts and also - beside a dominating natural indigo blue and a natural yellow dye - a synthetic red Azo dye, a colour that has been invented in the mid 1880ies and that has been available in the remote areas of the Middle Atlas from the early 20th century on. Despite the worn + stained condition a production date in the early 20th century can be concluded. |

|

|

(16) women's wrapping textile 'tahraoukht' (arab. 'haïk'), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 410 x 130 cm (161,4'' x 51,2''), early 20th cent. This example contains very few fine industrial cotton yarns (3 ply machine spun) in the design parts while the two colours, an indigo blue and a dark brown are obviously natural. Although in overall good condition (except the holes caused by the use of the fibulae) the absence of synthetic dyes makes it likely that this textile is older than the previous one. |

|

|

(17) women's belt 'abkass ouziza', Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 585 cm (230''), first third 20th cent. The woolen parts are dyed with an indigo blue and a probably natural brown. The silk parts seem to contain synthetic dyes. The small silver-plated copper sequins are known to be used until ca. 1930/40. A production in the first third of the 20th century can be assumed. |

|

|

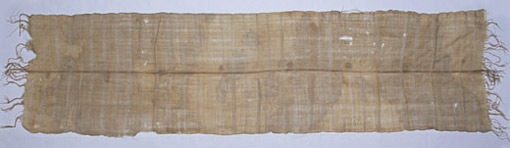

(18) men's wrapping textile (arab. 'haïk'), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 435 x 120 cm (171,3'' x 47,2''), wool, silk (?), third quarter 20th century (information given by the original owners when collected in the field) . The weaving width is not wider than 120 cm (ca. 47''). |

|

|

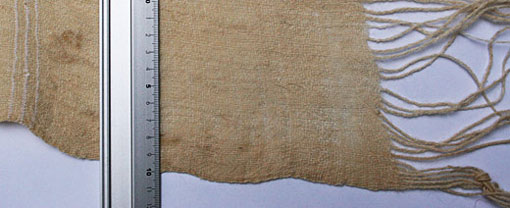

(19) men's wrapping textile (arab. 'haïk'), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco, 400 x 100 cm (157,5'' x 39,4''), wool, silk (?), early 20th century (information given by the original owners when collected in the field). Also this example shows a weaving width of not more than 100 cm (ca. 40''). Therefor it is logic to find intact selvedges in the 'taritat' veils even if the ground fabric is taken from an old wrapping textile such as this one (as described by Marcel Vicaire). |

|

As can be seen in the above examples, such textiles survive in very varying condition: some are fragmented through use, mildew, moth or mouse damage, others are well preserved. The probability of a textile surviving to the present day is no different in the Ahel Telt region to elsewhere. If other textile types have survived for a century or more, so should 'taritat' veils. The headbands, undoubtedly made in the Ahel Telt region, have a similar fine plainwoven structure, but it is possible that some of the men’s haiks were bought in from professional craftsmen, presumably in Taza, the main market town north of the territory of the Ahel Telt. If some haiks were bought in or made on demand, the fine, loose plainwoven ground fabric for 'taritat' could have been produced the same way. But it is also probable that at least some of it was woven locally. |

|

|

(20) detail of a headband 'tachedat n'tritat' >>(11), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco. The structure resembles the one of the 'taritat' veils and the men's wrapping textiles (arab. 'haïk') and bears witnesses that the Ahel Telt weavers have certainly been familiar with the production of this balanced plainweave or woolen muslin. |

|

|

(21) detail of a men's wrapping textile (arab. 'haïk') >>(18), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco. The half transparent balanced plainweave or woolen muslin structure is similar to the one of the 'taritat' veils. |

|

|

(22) detail of a men's wrapping textile (arab. 'haïk') >>(19), Ahel Telt (Beni Ouarain confederation), north eastern Middle Atlas, Morocco. The half transparent balanced plainweave or woolen muslin structure is similar to the one of the 'taritat' veils. The irregularity of the fabric makes it quite likely that the textile is of local origin rather than having been woven by a professional weaver in workshop circumstances in Taza. |

|

|

(23) detail of a 'taritat' (4). The presence of the decorative cotton bands on just one side of the textile suggests that the fabric has been cut from a larger men's wrapping textile (arab. 'haïk'). Again also the structure resembles the one of the headbands and the men's haïk. |

|

|

(24) detail of a 'taritat' (4). The opposite end of the textile is rolled up, sewn and also the fringes are sewn to the fabric what underlines that the fabric has been cut down from a larger textile with only one original end left. This fact matches exactly with the method described by Marcel Vicaire. Both selvedges however are intact as the weaving width of 98 cm (ca. 39'') matches with the original weaving width of the haïk. |

|

|

(25) detail of a 'taritat' (6). The textile shows quite significant wear overall. The selvedges are intact however. |

|

|

(26) detail of a 'taritat' (8). The fabric is thinned out all over the surface of the textile. None of the selvedges or ends has remained. This example shows every significant attribute of a textile that has been in regular use for a very long time. Field records underline that these textiles had been in every day's use in the period before the French protectorate. Meanwhile in the period since ca. 1920/30 these textiles have only been worn in special occasions, such as traditional weddings. |

|

|

(27) detail of a 'taritat' (10). Even in this heavily damaged fragment parts of the original selvedge can be found. Another clue that in the traditional way of manufacturing such veils the fabric had never been cut along the selvedges. |

|

| (28) detail of a women's wrapping textile 'tahraoukht' (arab. 'haïk') (15) |

|

|

(29) detail of a women's wrapping textile 'tahraoukht' (arab. 'haïk') (15). The weft faced weave is obviously too dense and too heavy for a veil, namely for a fabric that has been described as "en mousseline de laine, armure toile" (of woolen musline, balanced plain weave) by Marcel Vicaire.

|

|

|

(30) detail of a women's wrapping textile 'tahraoukht' (arab. 'haïk') (16) |

|

|

(30) detail of a women's wrapping textile 'tahraoukht' (arab. 'haïk') (16) . Motives and technique resemble the ones found on the headbands. |

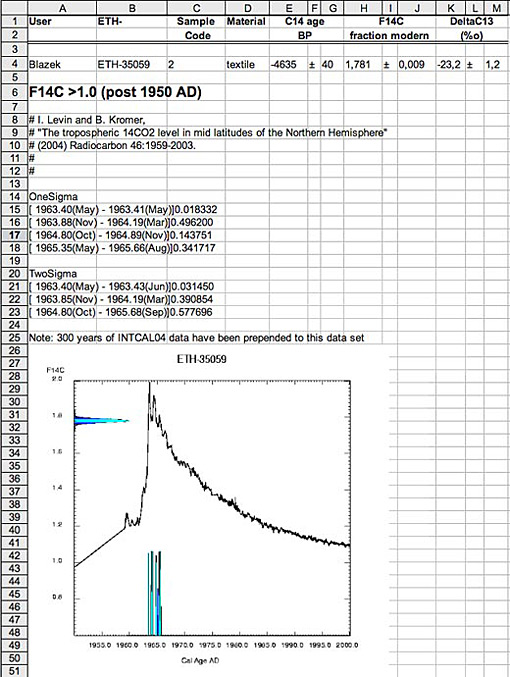

| Radiocarbon tests of certain textiles of the 'taritat' group, which are, due to their perfect condition, likely to be among more recently made examples, have shown that they were made in the late 1950s and early 1960s, during the era of atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. These very specific results contradict Rabaté’s assumption of their even more recent production, from which she attempts to deduce proof of falsification. |

|

|

(31) C14 test document by the ETH Zuerich, ref. ETH 35059 stating a production date of 1963 - 1965 for 'taritat' (3). The result is particularly significant as C14 levels during the era of atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons reached a height that has never been reached before or after that period. |

| In summary, we may say that this book introduces subjects well worth serious discussion, but fails to bring structure and clarity to the matter, thus leading to further confusion. The controversial chapters are driven, first and foremost, by Rabaté’s personal opinions, which are too often bold expressions of insufficiently or inaccurately researched facts, leading to errors. |

|

|

(32) detail of a women's shawl 'tabrdouhte' (13) |

|

|

(33) detail of a women's shawl 'tabrdouhte' (14) |

|

The original of this article has been published in HALI , issue 158, London , December 2008. |

|

My special thanks to Mustapha Hansali and Abdelaziz Ryahi for all their help, knowledge and friendly co-operation in the research and preparation of this article. |

| A correct transcription of the tribal confederation's name is Beni Ouarain ( neither Beni Ourain, nor Beni Quarain or Ait Ouarain are correctly or commonly used terms in the region. The term Ait Ouarain appears in the ethnologic literature of the French protectorate's period quite frequently but seems to have been hardly used by the Beni Ouarain people themselves). In a German transcription the term Beni Warain is also commonly used. |

|

© all photos Gebhart Blazek except (2), screenshots from the film "Ait Haddidou (North Africa, High Atlas) - Dyeing a Cloth with the Plangi Technique" used with the personal permission of Norbert Mylius jun. |